Elon Musk has a great idea for rating the credibility of the media. But it’s not a new idea. In fact, it’s the foundation of the First Amendment.

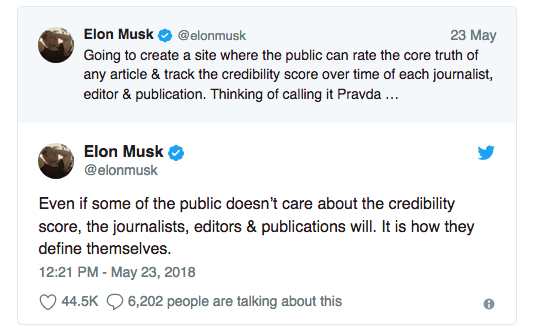

Perhaps you’ve read about his tweet (above). Journalists love to discuss this stuff. It’s what we do. Obviously he recognizes this.

He may not know there already are several sites that attempt to do just that, such as The Knife and Media Bias Fact Check and AllSides, as well as organizations that have been around for decades like MediaWatch, or places such as Snopes, or Politifact or FactCheck, all of which come at the same problem from a little different angle.

Of course, there are plenty of journalism organizations — like the Nevada Press Association and its counterpart in every state, as well as national groups and nonprofits and university-backed operations — that have been in existence nearly since the adoption of the First Amendment. They share the same goal as Musk’s proposed title for his site: The Truth.

In short, pursuit of the truth is the definition of journalism.

The fundamental principle behind the First Amendment is a marketplace of ideas, where everyone is free to say and write whatever they want. The best ideas, the theory goes, will rise to the top and be embraced by the most people.

It is very much a marketplace — a free-enterprise, largely capital-driven open exchange where people “rate” the core truth of every article, every journalist, every editor and every publication. They do so with their time and their money. It’s how this whole marketplace works.

Here’s the problem

Musk, though, somehow envisions this as a site — one stop, apparently — where all this could be sorted out. Here are some obstacles:

Who operates it? As soon as you put somebody in charge, it becomes subjective. Would Elon Musk’s site evaluate the veracity of articles about Tesla? Would it rate press releases issued by Space X? Would it weigh in on tweets written by Musk himself?

What’s the media? When Musk writes about journalists, editors and publications, he’s left out the most dominant media of the day — social. He doesn’t even mention radio or television. “The medium is the message,” Marshall McLuhan wrote, 30 years or so before the internet was invented.

What to evaluate? It makes my head swim just to imagine trying to rate every article, blog post, e-mail newsletter, tweet, YouTube video and Facebook post during the course of a day. That doesn’t count the 24-hour news cycle of television or the nonstop radio talk shows. Are we talking merely about editorial content or do we include advertising, as well?

What’s the criteria?

Here, I want to get into a bit more detail. I think it gets to the heart of the matter. What is the core truth?

Let’s take, for example, four paragraphs from a story about Musk’s conference call on May 3 about Tesla. This story was in Business Insider and written by Mark Matousek. I don’t know who edited it. Business Insider appears to be owned by Kevin P. Ryan, Dwight Merriman, and Henry Blodget. I don’t know if that matters.

During the Q&A segment of the call, Musk rejected a question from Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. analyst Antonio Sacconaghi, who asked about the company’s future capital requirements.

“Excuse me. Next. Boring bonehead questions are not cool,” Musk replied.

The next question came from RBC Capital Markets analyst Joseph Spak, who asked about Model 3 reservations.

“These questions are so dry. They’re killing me,” Musk said, before turning to Galileo Russell, a retail investor who runs a YouTube channel about Tesla. Russell was allowed to ask several questions about a range of subjects, none of which concerned Tesla’s financial health.

Are these paragraphs accurate? Well, there are audio tapes of the conference call and transcripts that we could check, so I’m going to say the quotes are what Musk actually said, and that the people who asked questions were really on the call. It’s tough to get a sense of the inflection with which Musk said them — was he joking, angry, rude, dismissive?

Is it fair? The writer used the word “rejected” to describe what Musk did. He then includes a sentence about a Russell being “allowed” to ask several questions, “none of which concerned Tesla’s financial health.” The implication, I think, is that Musk didn’t want to respond to tough questions from people who were potentially critical of the company. Instead, he preferred some softball questions from a fan. Is this the core truth — how everybody, including Musk, would characterize his response? There might be a dozen different interpretations by everybody on the call. How would you rate the fairness objectively?

Is it in context? Well, the short answer is no. I grabbed four paragraphs out of a longer story, which condensed a phone conference of several minutes (the transcript runs something like seven pages), about an issue with extensive background and angles. In fact, there were dozens of follow-up stories from this single conference call, ranging from Musk’s sort-of apology to analyses on whether it affected the stock price. In some respects, his tweet about Pravda could be seen as a continuation of the media reaction to a conference call that happened weeks ago. So what weight would you give the context of any of this?

These are basic elements on which every journalist evaluates a story — his own or someone else’s.

But there is another element at work here — perhaps more significant than all these. Who reads the story?

If you want a core truth, it’s that people will read stuff they like, with which they agree and which entertains them, far more often than they will read something that challenges their beliefs, addresses uncomfortable or complex issues and is, for lack of a better word, boring to them.

And that’s the rule of the internet.

That’s where we are. We have sidelined the gatekeepers — the editors who decided what’s so important that it deserves to be on the front page — in favor of algorithms, filters and metrics. You can choose your own truth, knowing it’s been manipulated before it reaches you.

But that’s the way the game always has been played. You can call it clickbait, or the Page 3 girl or yellow journalism. You can attempt to woo readers as the World Weekly News (“The World’s Only Reliable News”) or the Wall Street Journal.

We all rate everything we consume every day. If we like it, we go back. If we don’t, we go elsewhere.

It’s why the First Amendment works.

Nevada Press Association The best in Nevada journalism since 1924

Nevada Press Association The best in Nevada journalism since 1924