By Barry Smith

Much has been written about the colorful and controversial character named Christopher (Kit) Carson — studious biographies, every history book about the West, plenty of newspaper articles and whole series of lurid dime novels.

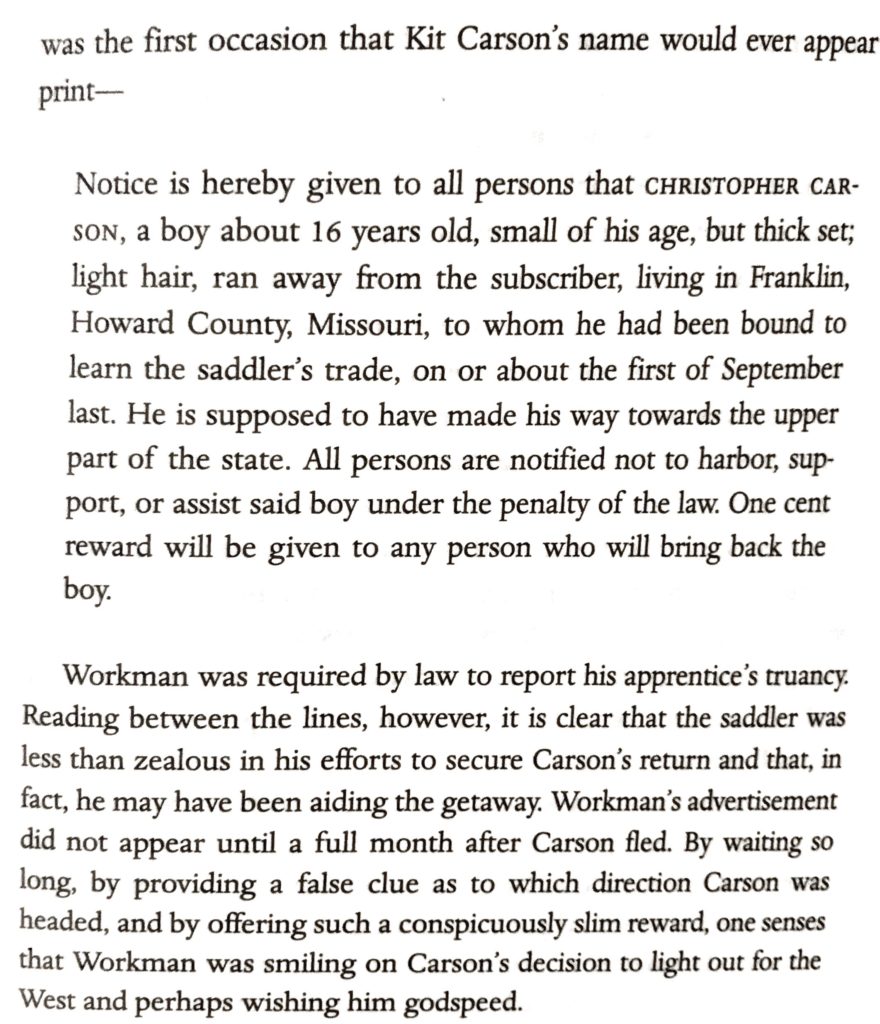

But the first time his name appeared in print was a public notice.

It was in his hometown newspaper in Missouri, after a 16-year-old Carson abandoned his apprenticeship to a saddlemaker and ventured on his first trip to the plains and mountains where he eventually made his reputation as a frontiersman and trapper.

I’ve recently been reading Hampton Sides’s 2007 biography, “Blood and Thunder,” which is subtitled “The epic story of Kit Carson and the conquest of the American West.” It’s thoroughly researched and well written, providing the kind of detail that brings the sweep of history down to human scale.

Not far into the book comes this page:

I’ve lived in Carson City for more than 20 years. For the first 10, I was editor of the local newspaper, the Nevada Appeal. For the past decade, I’ve been director of the Nevada Press Association, where part of my job is to advocate for public notices in newspapers. Most days I walk past a statute of Kit Carson on the capital grounds, a block from my office.

I’ve testified dozens of times in front of the Nevada Legislature, appeared before boards and commissions, written articles and been quoted widely on the importance of public notices as, among other things, a historical record of official business. In fact, just a couple of weeks ago we hosted a webinar on the topic of public notices in newspapers.

But I had no idea, until I turned to that page in “Blood and Thunder,” of the convergence of the history of the place I live and the occupation I follow.

But I had no idea, until I turned to that page in “Blood and Thunder,” of the convergence of the history of the place I live and the occupation I follow.

I suppose there’s no real significance in this nugget of serendipitous trivia. It was just one of those knocks on the noggin when you wonder, “How did I not know this before?”

There’s no doubt I’ll find a way to work this into some future legislative testimony.

In the meantime, let me make the point I have been arguing for 10 years without the benefit of this bit of evidence: Print publication is the record of our history. It can be preserved on microfilm. It can be shared and spread in the modern era by digital media and the internet.

But I fear whole eras are being lost if the only place that words and images are being recorded is the ethereal mist of electronic communication.

This public notice, published in Franklin, Mo., in August 1826 has been preserved, passed down and known (except by me) because it involves one of the most famous people in the history of the American West. It is proof of a fact of Carson’s life.

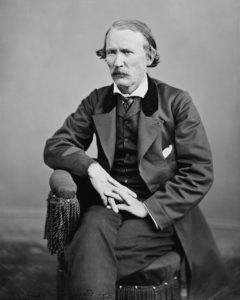

Carson’s name is carried not only by Nevada’s capital, of course, but by the river that runs through it, the mountain range that overlooks it and the valley on its southern boundary. A county in Colorado, museum in Taos, N.M., several lakes, a military post and all manner of other geographical locations also bear his name. His legend is as big as the states he traversed and as long as the trails he explored.

His reputation has waxed and waned, from American hero and champion to mass murderer and villain, and is settled for the moment on a more complex and nuanced portrait of a man and his times.

Much that was written about him contained legend and lore — certainly the dime novels were fiction attached to fragments of fact, similar to today’s movies that claim to be based based on a true story.

I have more to read in “Blood and Thunder,” and much to learn about Kit Carson. But I now know for a fact that he fled his apprenticeship as a boy. It was in a public notice in the newspaper.

Nevada Press Association The best in Nevada journalism since 1924

Nevada Press Association The best in Nevada journalism since 1924