A bill coming up for hearing this week in the Nevada Legislature would strike two blows against a fundamental precept of the state’s public-records statute.

The bill, SB28, was proposed by the Nevada League of Cities and Municipalities. It’s scheduled to be heard by the Senate Government Affairs Committee at 1:30 p.m. Wednesday.

One portion would set a fee of 50 cents “per page or, for a request for a record to be delivered electronically, 50 cents per the equivalent amount of electronic data that, if printed using a type size not greater than 12 characters per inch, would fill a page” to copy a public record.

In other words, if you want a 100-page PDF, government would be able to charge $50 — for hitting the ‘send’ button.

Another portion of the bill would define ‘extraordinary use of personnel or technological resources’ to fulfill a records request as anything more than 30 minutes.

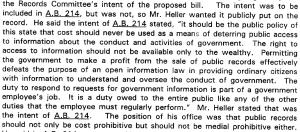

The key words are ‘actual cost.’

It does not cost 50 cents to copy a page — even though the law allows government to charge that much. Already, they are trying to generate revenue from a copy, rather than simply recovering the actual cost.

If I can copy a document in my office for a penny or two, or have Office Depot make copies for me at 10 cents each, then agencies are charging at least five times the actual cost.

Under the bill, however, they would take that fee to an absurd level by charging 50 cents for each page of an electronic document — the actual cost of which should be nothing.

Why would the Nevada League of Cities and Municipalities want to do such a thing?

To be generous here, the purported reason is to recover costs of massive records requests. All this language comes under the ‘extraordinary use’ section, intended to give some relief when someone wants thousands of documents, or records that cover several years, or that may in some other ways require an ‘extraordinary’ effort.

I agree that there should be some way to account for large, complicated requests for records. That’s why the law allows up to 50 cents a page.

Unfortunately, some governmental agencies use the ‘extraordinary’ clause to discourage people from asking for copies of public records. I have seen responses recently from Nevada governments estimating copying fees of more than $10,000 and $5,000.

But let’s be clear. The intent of the law — as stated when it became law, and upheld in court — is that it’s not to be a revenue center for government.

Here are minutes from the 1997 hearing on AB214 when Secretary of State Dean Heller introduced the bill:

Further, below are two quotes from District Judge Susan H. Johnson’s in 2009 when she ordered the Clark County School District to turn over e-mails at no cost to Karen Gray:

‘If anything, taking the CCSD’s position in its papers as true, the actual retrieval/separation of all e-mails generated by seven (7) school board trustees should expend little of the technology staff’s time in making a few computer key strokes.’

‘In short, if CCSD believes certain e-mails generated by its school trustees contain confidential information, it is the one who should bear the expense of review and redaction, if any, as well as provide MS. GRAY an explanation as to why the public record will not be produced.’

Two important principals were confirmed by Judge Johnson: Hitting a few keystrokes to search for emails is not an extraordinary use of personnel. And the expense of review and redaction is not the responsibility of the requester.

A third fundamental principle is contained in NRS 239.010 when it states: ‘ … all public books and public records of a governmental entity must be open at all times during office hours to inspection by any person …’

Therefore, just like reviewing and redacting, the cost of searching for records must be borne by the government, not the requester.

It’s not the public’s fault if a governmental agency can’t find its own records. I can hear, though, the bureaucrats complain that they can’t be expected to have all public records available at their fingertips. In the larger agencies, records may be stored like Indiana Jones’s Ark of the Covenant in a cavernous warehouse across town. And that very well may be true. Again, though, that’s the choice and the responsibility of the government as to where and how they store the documents.

You can see how easily the second provision of SB28 — 30 minutes for ‘extraordinary use’ — could be abused.

If two employees spend 10 minutes discussing a records request with a supervisor, the 30 minutes is gone. If it takes an employee 30 minutes to drive across town to fetch a document, it’s an extraordinary effort. If it takes 30 minutes to download a large file, that’s an extraordinary use of technological resources.

Nevada Press Association The best in Nevada journalism since 1924

Nevada Press Association The best in Nevada journalism since 1924